Christopher Jackson

This is a strange book to review since it has been almost entirely superseded by the actions of its ghostwriter. It is axiomatic among book reviewers that you must review the book and nothing external to the book, but that turns out to be impossible here.

For anybody living without Internet access these past months, here is the sequence of events.

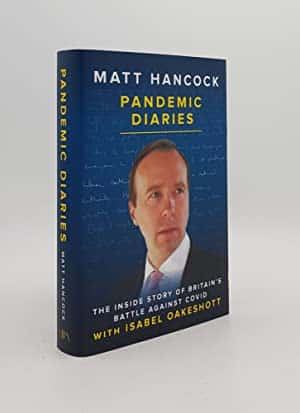

Matt Hancock was a busy Health Secretary, and former prime ministerial candidate with ambitions to digitise the health service. In late 2019, he began getting reports from Wuhan about a virus which would upend his and all our lives. He was a cheerleader for lockdown, and also – as he goes to considerable lengths to point out throughout this book – a driver of the vaccination programme. In May 2021, he began a marital affair with his aide Gina Coldangelo, and when an embrace between them was somehow – we still don’t know how, or by whom – photographed, Hancock was forced to resign.

Post-government he famously appeared on I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here, where he made more friends than some had expected. Pandemic Diaries was intended to continue his rehabilitation. However, it was written in a spirit of what now seems gullible collaboration with the journalist Isabel Oakeshott. In the writing of the book, Oakeshott was given access to all of Hancock’s What’s Apps. After the book was released, Oakeshott, pleading the importance of journalism, handed all the messages over to The Telegraph, who proceeded to publish a series of immensely unflattering stories about Hancock which undid much of the painstaking work of rehabilitation.

As a result, the book has acquired a sort of unexpected intertextuality, whereby we can now see that what is said in the book is a pared-down and smoothed-over version of what was said in real time, now there for all to see in the pages of the Telegraph.

The juxtaposition between the two can often be comic. For instance, on the unhappy day to which we all know this book is building – the disastrous day when Hancock’s affair is broken by The Sun – Hancock begins his entry with a knowing dissertation about love.

What price love? I’ve always known from the novels that people will risk everything. They are ready to blow up their past, their present and their future. They will jeopardise everything they have worked for and everything that is solid and certain.

The tone is of an earned, rueful wisdom, and we are invited to consider Hancock as a sort of modern Antony or Othello, undone by human failings, one who ‘loved not wisely, but too well’. Perhaps he is but he comes across differently to readers of The Telegraph in the following What’s App exchange on what was presumably the same day:

Hancock: How bad are the pics?”

Special adviser Damon Poole: It’s a snog and heavy petting.

Hancock: “How the f— did anyone photograph that?”

Gina Coladangelo: OMFG

Hancock: “Crikey. Not sure there’s much news value in that and I can’t say it’s very enjoyable viewing.”

It is The Telegraph version, sadly, which in all its awkwardness has the real flavour of lived experience. Incidentally, I find huge sadness and a sort painful dignity in Coladangelo’s acronym, and I suspect many readers will feel especially sorry for her.

Perhaps in a ghoulish way it is good to have both versions, but there is an overriding sense that we know more than we’d like or ought to about the whole thing. Anyone who enjoys reading about the destruction of other people’s lives and imagines themselves immune from similar treatment has ceased to think themselves fallible on another day.

Of course, the question of government by What’s App has now been taken up as a live issue in direct response to the Oakeshott leaks. It seems unlikely that it’s any worse as a form of government, to paraphrase Churchill, than all the others which have been tried. In fact, the real thing at issue has always been between responsible and irresponsible government.

How does Hancock, and how does the political class, come off in Pandemic Diaries? It’s a mix. The book conveys Hancock’s Tiggerishness very well in the clip of its prose. Developments are often greeted with a one word exclamation. “Stark,” he writes on hearing news that the NHS could have a deficit of 150,000 beds and 9,000 ICU spaces. “Fuck,” he says, on hearing that Nadine Dorries has tested positive early on in the pandemic. “Amazing,” he exclaims when he hears that 4,000 nurses and 500 doctors have rejoined the NHS in 24 hours on 21st March. This turns out to be his favourite word and is levelled at good news on the vaccination programme and at the exploits of Captain Sir Tom Moore. Its obverse: “Very sobering” is deployed when the Covid deaths spike, as they do saddeningly throughout the book.

The style conveys someone in a hurry, and one is left in no doubt that Hancock had the energy and ability for the job. In fact, he probably had every right to imagine he had a good chance of being prime minister one day. Although his official mentor is George Osborne, who crops up occasionally in the book, Hancock feels more reminiscent of Blair; in fact, he sometimes seems to have self-consciously modelled himself on him. Blair’s astonishing electoral success marked the younger Conservative generation who began to imagine that power would never come their way if they didn’t somehow emulate him.

It was Clive James who said of Richard Nixon that he could handle the work; Hancock was the same. You can feel that the Health Department, unwieldy and daunting a brief as it is, was in some way too small for his ambition, and that he role wasn’t too much for him. He was equal to the task, and throughout you have a sense of him moving his agenda forward: he comes across as a skilled and astonishingly hard-working minister.

Even so, I don’t think the book is likely to make people especially eager to enter politics. This might be because we all know that whatever is going on in the book, our hero is hurtling with alarming pace towards downfall and public humiliation.

But this isn’t the only reason. In the first place, large sections of the book seem to detail something like a toxic work environment which few would wish to join. The undoubted villain of the book is a certain Dominic Cummings, which are the passages I most enjoyed reading, since he seems to get under Hancock’s skin very easily, leading to some entertaining and quite astute rants: perhaps we are never more insightful than when we hate. On March 31st 2020 we get the beginnings of a theme which will recur:

Amid all this, Cummings’s morning meetings have turned into a shambles. I can’t say I’m shocked. The feedback is that no one really knows who’s meant to be talking about what, to whom, or indeed whether they’re supposed to be at that meeting or the one an hour later….Managing No. 10 is a massive and extremely frustrating part of my job.

As much as one can sometimes feel a bit frustrated with Hancock himself, this rings true, and there is real relief in the book which you suspect must have been felt by all the characters in the book, including Boris Johnson, when Cummings leaves.

Government itself seems ad hoc, and Boris himself very often reactive. Of course, this might be an effect of the genre: we only see Boris when Hancock goes to see him, and then as it’s all being told through Hancock’s eyes. But there seems to be a sort of fatal passivity about Boris, the ramifications of which played out in March 2023 before the Privileges Committee.

Above all, we’re beginning to realise that these were just very unusual times. That is perhaps the biggest hindrance towards enjoying this book: the events it describes were both appalling and recent. What a terrible thing the virus was and is; how terrible lockdown was. There is no doubt for this reader that Hancock found a single-minded groove over lockdown which to some extent kept him sane and able to function under pressure. It was this coping mechanism which led to some of the worst What’s Apps in the Oakeshott leaks, including the infamous one where he considers threatening to block a local MP’s disability centre. By a certain point, he had come to believe in lockdown as, to use another infamous phrase, a ‘Hancock triumph.’

The reader is left with the sense that perhaps Hancock went a little bit mad. But one feels that somewhere in his make-up is a man of admirable energy and commitment. He’s not quite in the Randolph Churchill, Joseph Chamberlain and Ken Clarke category of almost Prime Ministers, but a couple of rungs down, with Nick Clegg for company.