Robert Golding

There is a story that David Hockney tells often about being a young film enthusiast in Yorkshire, watching black and white Laurel and Hardy movies. Seeing the long shadows, he realised that Los Angeles, where they were filmed, must experience a lot of sunshine. Accordingly, he resolved to go there.

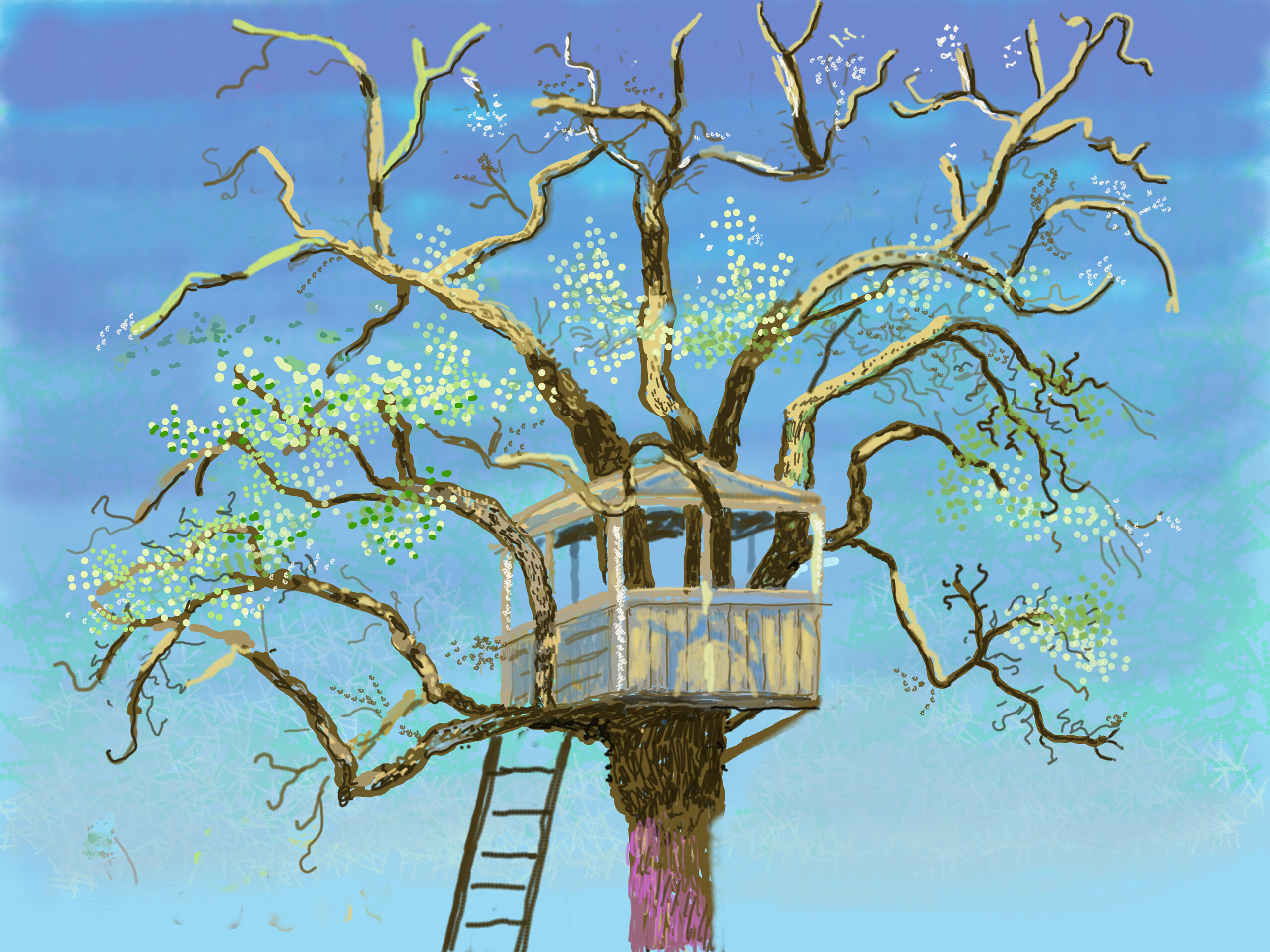

Today, Hockney is still enthralled by light – as you can see in the tree house picture with which this article is illustrated. Here is something like that same light which attracted the young Hockney, still attracting him at the age of 83. But this isn’t Californian light – it’s the light of Normandy, at the house called La Grande Cour, where he has lived in isolation since 2018 with his lucky assistants Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, known as J-P and Jonathan Wilkinson, together with his dog Ruby.

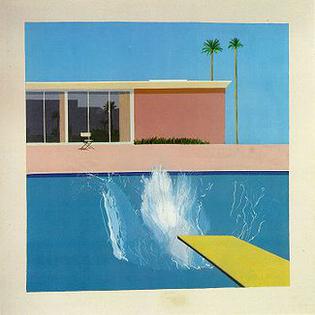

And, of course, unlike the images of California – such as 1967’s A Bigger Splash, for which he is still most famous – Hockney’s new works are not essays in paint but drawn on the free Brushes app on his iPad. The layered nature of paint has been replaced by marks which bear – perhaps a little too obviously – a digital mark: the dots, the pixelly sky.

“Ratified by time and the art market, David Hockney has never been one to mind what people say about him.”

To move forward but to stay the same – as with his hero Picasso, Hockney’s way of seeing is always his, no matter how much his method might be bound up in new technologies, and advances in his own understanding of what makes art.

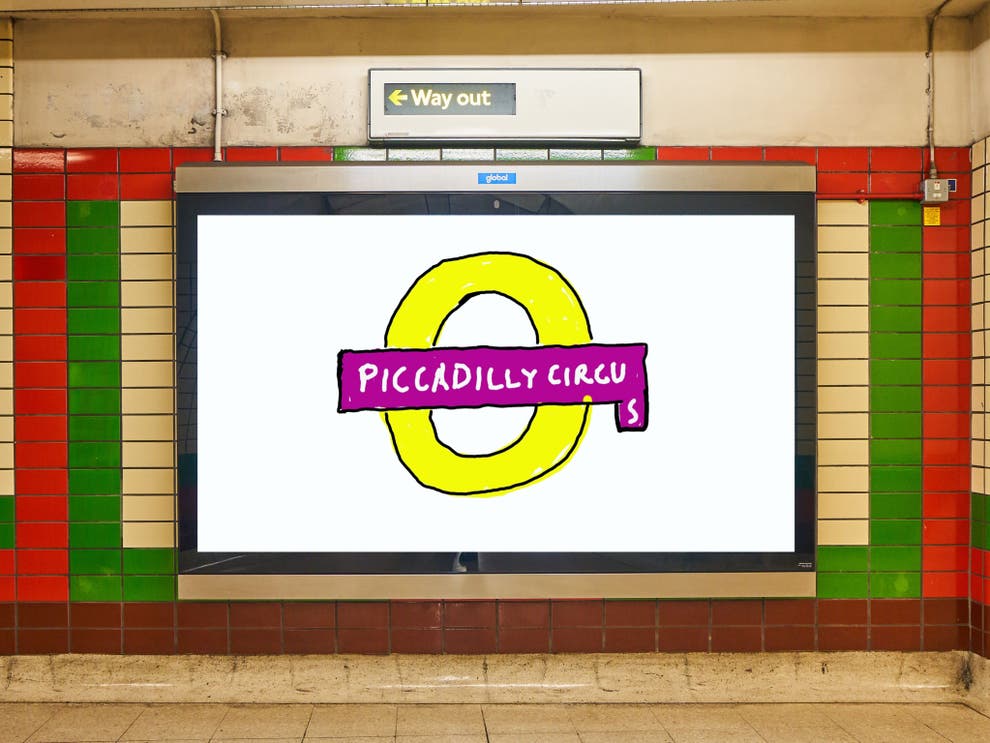

The eye always remains forensic and supremely confident – ratified by time and the art market, David Hockney has never been one to mind what others say about him. Right now that’s probably a good thing as the art world has rounded on him for his Piccadilly Circus tube sign, drawn with a whimsical humour which looked to struggling artists like cosy facetiousness – the ‘s’ in ‘Circus’ dropped off the end, the gag somewhat too easy, like someone used to having his jokes laughed at by acolytes.

The Royal Academy exhibition The Arrival of Spring hasn’t been particularly well-received either. It’s doubtful that the criticism will affect the supremely confident Yorkshireman. A contrarian spirit seems to replicate itself in many successful people. This is so with Hockney, whose love of life appears to begin in a healthy contempt for all do not share it, and who prefer to conform. ‘Boring old England,’ was his famous reasoning for leaving his home country for LA in the 1960s.

To study Hockney’s life and his art is to get to know the benefits of particular kind of bluff decisiveness. The octogenarian has always known his next move – or found it materialise it before him as a thing to be straightaway acted upon.

In Paris in the 1970s, he realised too many people were visiting him and that he wasn’t getting enough work done – keenly alive to the danger to his productivity, he straightaway upped and left. When he stayed on in England after Christmas in 2002, he realised that he had been missing the seasons of his native Yorkshire, and rearranged his life to take advantage of it.

Here he is describing the move in 2013’s A Bigger Message: “I began to see that that was something you miss in California because you don’t really get spring there. If you know the flowers well, you notice them coming out – but it’s not like northern Europe, where the transition from winter and the arrival of spring is this big dramatic event.”

“I began to see that that was something you miss in California because you don’t really get spring there.”

David Hockney

Then just before lockdown, came another example of the Hockney decisiveness: during a brief visit to Paris, he realised that Normandy attracted him sufficiently to be worth moving to. Here he is telling the story to Martin Gayford in the pair’s excellent collaboration Spring Cannot Be Cancelled: “It happened like this. We travelled to Normandy after the stained-glass window at Westminster Abbey was opened. We went through the Eurotunnel, via Calais. We stayed in this lovely hotel at Honfleur, where we saw this sunset.” In time, J-P was dispatched to an estate agents: “When we came in and saw the higgledy-piggledy building and that it had a tree house in the grounds, I said, ‘Yes, OK – let’s buy it’.”

“This house is for David Hockney and he wants to paint the arrival of spring in 2020, not in 2021!”

Fame had come for Le Grand Cour – destined no doubt to be a tourist attraction to rival Monet’s lily pond at Giverny. Of course, this freedom is partly the freedom of the immensely successful.

In Gayford’s telling of the house purchase, the sense of Hockney’s importance is evident when J-P is quoted as saying impatiently to delaying builders: “This house is for David Hockney and he wants to paint the arrival of spring in 2020, not in 2021!” One senses that he has surrounded himself with the right people; Hockney has the gift for friendship and loyalty. This hasn’t necessarily always been to the good: there are signs in The Arrival of Spring that a certain cosiness may finally have seeped into his work to its detriment.

Certainly the current exhibition which has been widely panned in the media, except by his friend-reviewers such as Jonathan Jones of The Guardian and Martin Gayford at The Spectator.

So are the negative reviews fair? Undoubtedly some of them are written with the pantomimic disdain which journalists sometimes level at people who have become more famous than them. One example would be the overdone headline in City AM: “I hate these paintings in my bones.” If we look at a painting this way, what emotion do we have leftover for atrocities of war?

Besides, in among the sameiness, there are magnificent images here. I was taken particularly by a sequence of images of the sun rising over the slopes that surround Hockney’s new home. Hockney has rightly objected to the idea that you can’t paint a sunrise or a sunset by pointing out that such things ‘are never clichés in nature’. Here we see the old cliché of the yellow orb with tentacles of yellow seeping out of it rejuvenated to some extent: there is a lovely passage where the tree in the foreground takes the red of the sun, and becomes aflame with red, like something Moses might have seen.

There are other such moments – especially where Hockney reminds us that the iPad is especially good at handling complexity of space. One such example is No. 340 (see below) which directly recalls – and in recalling, competes with – Monet.

It’s worth restating that Hockney is an intensely competitive artist – his career is a reminder that there is nothing wrong with that. Once we have decided what to do, we may as well attempt to do it as well as anyone has ever done it before. The attempt may fall short, but will likely provide us with the energy we need to do our best.

An exhibition I attended at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2014 called David Hockney, Printmaker, showed him wholly able to assimilate Japanese pictures – Hokusai is another hero of his – and he remains an essentially competitive artist: the 2012 exhibition A Bigger Picture– also at the Royal Academy, was a direct challenge across the centuries to Paul Cezanne.

Besides, in this instance, Hockney doesn’t fall short. The entire picture is sumptuous, an act of deep and respectful noticing – to hate this in one’s bones would be in the regrettable position of hating life to one’s bones. Especially good are the dots in the bottom left, where three or four kinds of reflection are rendered alongside water and things which might be bobbing on the surface. This is done all at once with great joy and even bravery.

Nobody with any sense would claim that Hockney can’t draw a face…it’s just that here he’s chosen not to

There are other virtues to this exhibition. The iPad – as Hockney has pointed out – is very good for immediacy. There is no need to set up materials, instead you can simply get drawing – as in No. 370 beneath. This picture has its literary antecedent in Philip Larkin’s poem ‘Sad Steps’:

Groping back to bed after a piss

I part thick curtains, and am startled by

The rapid clouds, the moon’s cleanliness.

Here Hockney, doing the same, is equally startled – and again, what’s good is the journey of the moonlight through the clouds onto the edges of the bushes. We are told here that moonlight on a dark bush isn’t moon-coloured – it’s actually a kind of turquoise. We are also shown how moonlight doesn’t quite get in between all the way into the bushes; the image is a precise assessment of moonlight’s force and power. Even the most radiant nights have numerous hiding-places.

But there are problems with the exhibition too which one’s admiration for a lifetime of extraordinary achievement cannot quite oust. Samuel Johnson once wrote that a book that’s fun to write cannot be fun to read. When considering what might be wrong with The Arrival of Spring, Johnson’s remark is a useful place to start.

‘I think I am in a paradise,’ says Hockney to Gayford in Spring Cannot be Cancelled. While these images have rightly been praised for their exuberance, they remind you a little too much that Hockney is happy. The compositions are too often simplistic, and I am a little confused, having loved the accompanying book, that there isn’t greater diversity of subject matter. In the book, we see images of the artist’s foot, and of his iPad which would have made for a less repetitive exhibition.

Falsity in art can sneak in with terrible proclivity

Furthermore, the image contains not a single face. This isn’t because Hockney can’t do it – nobody with any sense would claim that Hockney can’t draw a face; in fact he’s probably the best draughtsman alive. It’s just that here he’s chosen not to. It might be that he has decided that spring is his subject – but if so, he needn’t have excluded the rest of life around him. We experience spring in relation to other people – as we’re almost tired of learning, in our little locked down bubbles.

Perhaps the timing of their composition might also have made them age more. They were no doubt begun in a more contrarian spirit during the beginning of lockdown than we can now recall, full of a defiant desire to show the world that there are worse things than being circumscribed to just one place.

But falsity in art can sneak in with terrible proclivity. As an example, Larkin’s poem ‘Sad Steps’ spins to a false conclusion, about how youth cannot come again but is ‘for others undiminished somewhere’. It is a crystalline poem of marvellous technical brilliance reaching the wrong idea – because if youth is indeed irreversible then it is diminished for everyone everywhere all the time. The poet isolates himself in a bogus despair.

Hockney may perhaps be making the opposite mistake – readers of his History of Pictures (also produced with Gayford), may finish the book still in the dark as to why he makes them, besides the pleasure of being good at making them. Certainly, these images sometimes feel ultimately untethered from meaning, or perhaps insufficiently urgent in their pursuit of truth. Look at No. 259, for example, and then look at any Van Gogh – whom Hockney is also ostensibly competing with here.

In the Van Gogh you’ll find that things are never quite the colour to Van Gogh as they are to you – and your sense of the world is accordingly changed utterly. In Hockney, except for the few passages of painting I have isolated, they are almost always the colour you expected them to be. They look very very green. Hockney is as exuberant as Van Gogh, but Van Gogh is more alert to what the world actually looks and feels like, and so is the greater artist, and sometimes by a long distance.

This brings me to a bunch – namely, that there’s a slight sense that Hockney may not have avoided the dangers of sycophancy in those around him. He has always been very good at self-editing but I wonder if this business of sending his drawings out to his friends – among them Martin Kemp, Gayford and Jones – has led to the creation of an echo chamber and a slight diminishing in standard. Gayford is a brilliant critic and writer, but every page he writes with Hockney breathes his excitement at being in the great man’s company. Such people do not tend to tell you when your game has dipped.

Exuberance, in short, isn’t enough in itself. You have to have setback, difficulty, and vexation. We might distinguish between intense and casual exuberance, with Van Gogh in the former category, and Hockney – at least in The Arrival of Spring – all too often in the latter.

And yet this exhibition is still worthwhile in that it shows a worthy intention – to show the spring and to capture its beauty. Hockney’s career is a reminder to all of us as to what can be achieved if we find what we love, and work hard. Back in the 1960s, Hockney had a note next to his bed which read: ‘GET UP AND WORK IMMEDIATELY.’ If nothing else, this exhibition is a reminder of the tremendous grace of hard toil. And if you wish he’d sometimes worked harder to challenge himself then that only reinforces the lesson.

David Hockney’s The Arrival of Spring is at The Royal Academy from 23rd May until 26th September

Spring Cannot be Cancelled by David Hockney and Martin Gayford is published by Thames & Hudson priced £25.