As the world comes out of COVID-19, Iris Spark looks for lessons from art created during the Spanish flu pandemic about where we go from here

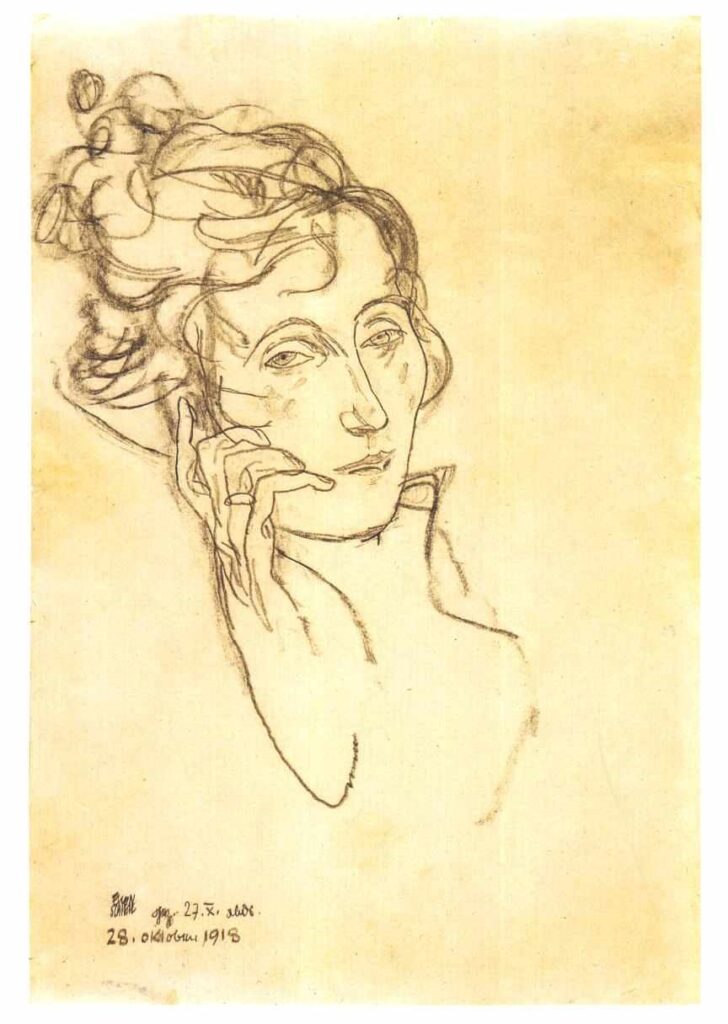

Edith Schiele, Egon Schiele, 1918

Consider this woman above. Unless we were to look closely at her, we might not know that she is set to die tomorrow. It’s true that her gaze is melancholy, but we might miss that her sadness has a leaden weight to it, distinct from the sadness we see in many romantic portraits. The clue to her condition is her gnarled and crooked hand, which tells the rapid encroachment of death more than her face, which still – heartbreakingly – has youth on its side. The more you look, the more signs of the seriousness of her condition are brought home. There are the strokes of discoloration on her cheeks. The lips are thin, a sign of the cyanosis which accompanied a deadly case of influenza.

The woman’s name was Edith Schiele, and she was married to that brief star of the modernist period Egon Schiele, whose works today can fetch as much as $40 million. Egon himself would die three days after drawing this picture. He was 28. It was an unhappy end to a life about to take off. As inauspicious as this story might seem, as we seek to emerge from the other side of the pandemic, it is a useful place to start if we wish to consider what can be learned from a study of the last pandemic about our current direction of travel.

We all know the statistics about the pandemic: the numbers dead or infected; and the jobs lost. But the data does not tell the full story.

Modern Family

Statistics blur over time; what’s left is the poetry and the art which a society creates. If we consider the so-called Spanish flu pandemic, which raged from 1918-1919, and which killed 100 million people, and infecting 500 million, we can see clearly in the era’s painting a trajectory which might well prove relevant for our times as we implement our vaccination programmes.

We have to start with an acknowledgement of the enormity of what has happened to us with the pandemic. This was evident too during the Spanish influenza. It can be seen, for instance, in the pictures Schiele made towards the end of his life. One is The Family (1918) – one of his last, and it would remain unfinished. This is a picture which in its mood is capable of placing us back in February 2020. It contains the foreboding of a vitality about to be stymied.

In this picture, two things alert us to the tragic state of affairs about to engulf the family: the first is the artist’s decision to depict his unborn child as if he wished to personify a child who would not survive the womb. The second is his painting of his own expression as blank and melancholy, his skin as jaundiced.

The baby might stand as a symbol for all the unborn projects which are stymied by the arrival of disease. But the definition of the musculature and the solidity of the forms make one feel uncomfortable about calling this an entirely pessimistic picture: there is will to endure here, and we can’t say it is any the less important simply because, in this instance, nobody in the picture survived.

Schiele, The Family

The picture is a reminder that the sheer oddity of what we have come through needs to be reckoned with and assimilated.

Fever Pitch

But surveying the art which arose out of 1918 pandemic, the most noteworthy thing is how difficult it is to depict illness. In pandemics we seem to enter a disjointed dreamscape. Illness isolates us, cuts us off from the solidity of the world. It partakes of the insubstantial, and can only be communicated in kaleidoscopic colours and the pictorial language of dreams.

In 1918, those artists who did experience a brush (or worse) with the Spanish flu, had already begun to intuit life as being at its core somewhat feverish and strange. This means we cannot always see how the influenza affected artists – they were, in some sense, feeling rather fluey about life beforehand.

Most notable among these was Edvard Munch (1863-1944) who also contracted the flu and produced two portraits (see opposite) about the experience Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu and Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu. In the first, Munch is depicted in a seated position with a blanket over his knees. The sheet beside him seems to be developing into a face, as if artist or sitter is hallucinating. The detail of his face is subservient to a swirl of colour. But how different is this picture philosophically to 1893’s famous picture The Scream?

When I talk to art specialist Angelina Giovanni she explains: ‘It’s very interesting that in the case of Munch – probably because themes of loss and death had already been present in his work – the way he depicts himself is no different in terms of style. Instead, it has a certain linearity within his existing body of work.’

Giovanni explains that it is as if Munch found some sort of confirmation of his prior experience by falling ill. The world had seemed disjointed before; and it continued to feel so when the influenza struck him. Giovanni continues: ‘Munch can so effortlessly depict himself within his predicament that were it not for the historical information that tells us that the work was painted when he had contracted the Spanish Flu, we might not have been able to place it in a particular point in time.’

While pandemics might illustrate our vulnerability vividly, they might not fundamentally change our method of vision. The world is elastic, and will return to its former shapes and structures.

But there is also no doubt that pandemics create an atmosphere of reflection which can be harnessed in future years. When I catch up with Fake or Fortune star Phillip Mould, he says: ‘When you’re locked down, and you remain in your own habitat, it’s a more meditative cultural experience and you think about the outside world in a different way.’ Mould even wonders whether we shall have more full-length portraits in future, now that we are all looking at each from six feet away.

For Mould this meditative spirit is best captured by Lorna May Wadsworth’s superb still lives painted during lockdown, in which mere things – cups and vases – attain a meditative quality which, in his view, supersedes her previous work as a portrait painter.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919.

It was the American novelist Saul Bellow who once wrote that ‘Death is the dark backing a mirror needs if we are to see anything.’ The Spanish flu and COVID-19 pandemics caused a widespread awareness of mortality: what appears to happen is that our relationship to death is placed again under the microscope.

In 1919, the experience of finding oneself so suddenly vulnerable expressed itself visually.

Death Becomes Us

Egon Schiele was not the only major artist to be claimed by the influenza. The other was Gustav Klimt, who suffered a stroke and died as a result of catching the infection. He was famous at the time for his painting Death and Life (1916). Here we have a close approximation of what death meant to the early 20th century mind – albeit through the prism of an individual of genius.

Death hovers to one said of the main grouping, his clothing patterned with crucifixes. These religious symbols act as a reminder that as radical as we think him, Klimt inhabited a world where Christian imagery was more prevalent than it is in our time.

How are we to feel about the figures on the right? Are they detached from death – in a kind of legitimate bliss of colour, and shared bodily warmth? Or are we to feel that they are failing to be awake to the menace of death as shown by the Reaper on the left-hand side of the painting? It’s likely that the picture contains both interpretations.

For Philip Mould the art of this period presents a problem in that ‘it is always hard to be sure what devolves from the First World War and what from the flu pandemic.’ What is clear is that with death more prevalent, something like a medieval acquaintance with death had been transposed into a modern setting. This can connect us with primitive political instincts – as was shown in the 1920s rise of fascism and as may be evident also in the riots in the Capitol, Washington D.C. on January 6th 2020.

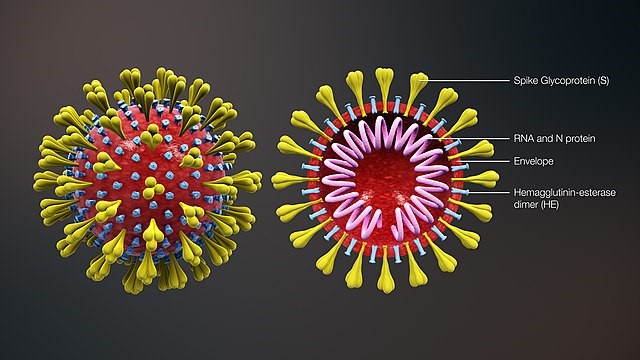

Of course, in our own times, death has been depicted somewhat differently. Whereas death is still symbolised in Klimt by the medieval figure of the Grim Reaper, today death is represented with scientific diagrams such as the one opposite. Such images give a different sense of death. Here the virus appears has something spherical but prickly, but undeniably alien: an intruder. The Klimt picture shows death is demonic – which is to say almost human. It is an indicator of how our society has shifted.

Cocktail Hour

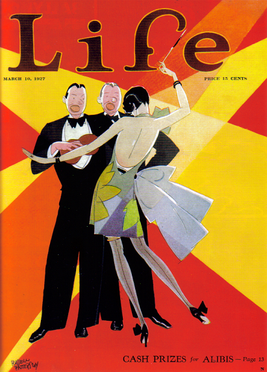

But what happens in the 1920s once society has recovered from a pandemic and we are able to interact confidently again? In the visual arts of the 1920s, we see the return of the line. The Art Deco style, as shown by the superb Russell Patterson illustration ‘Where there’s smoke there’s fire’ couldn’t be further from the blur of the Munch paintings. Society has returned to health. The owner of this body is again confident not just in herself but also in the bodily pleasure of smoking. Likewise, a renewed bodily confidence is again suggested in the cover of Life opposite which shows the joy of dancing – and again, all told in a strong line and healthful colours.

So might we find that once the world returns to normal we shall see the meditative aspects of our art today cede to something more dynamic, more fitting to the partying spirit?

That remains to be seen, of course, but as everyone knows the 1920s are not the end of the story. We find a move towards health and life in the art of the 1920s, but it is a fine line between this development and excess. In literature, the crucial text would be The Great Gatsby, in which F. Scott Fitzgerald’s own ‘crack-up’ is prefigured. His friend Ernest Hemingway would soon find his work affected by the excesses of drink – alcoholism would also lead to suicide.

In the visual arts, it might be said that the artistic world bifurcates along two vectors of greatness: towards Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). Both were active at the time of the Spanish flu, though neither experienced a sufficiently severe case for us to say with certainty how it impacted their creative output.

Picasso’s own commitment to the line was always, with the invention of Cubism, synonymous with the notion of fragmentation. He seems in his pictures from 1906 onwards to see round things – to intuit time and meaning at work within the appearance of a given object.

But by the time we reach Guernica (1937), his vast oil painting depicting the Spanish Civil War, we can see how he is no longer depicting the complexity within objects as some fundamental fracture in society. Here, we find the sort of visions which might be intuited in the work of Schiele and Munch with which we began. It is as if we are now confronted with their worst fears enacted.

Pablo Picasso, La Guernica, oil on canvas, 1937

So what had happened in the intervening time? The short answer, of course, is fascism and there will be few who have witnessed developments in America these past years who can be certain that once the deprivations of coronavirus have passed, we might not head in that direction.

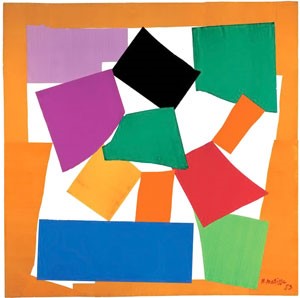

But the art of Henri Matisse shows a more hopeful story. In old age, he became a celebrator of simple colour, simple pattern, and graceful movement. If Picasso’s nightmarish canvas shows the fears of Schiele and Munch more than realised, then we might argue that Matisse’s scissor art in its childlike delight at colour and shape shows what they’d have liked to go on living for – they indicate something of the joy we all feel about the life which we all fear departing one day.

Perhaps all this is encapsulated in his great late cut-out The Snail, which he worked on after his stroke from 1952-3. It is an exercise in chromatic colour but it is the title which might strike us: since there is no sense in which this a realistic depiction of a snail we are liberated into feeling that Matisse is here showing us something of the feeling he gets from looking at one of nature’s humbler creatures.

Henri Matisse, The Snail, 1953, Gouache on Paper

In 2021, we should hope for just such an arrival in ourselves. Locked down in our homes we have seen the world at a slower pace, with more centredness, than we had been used to doing during our frenetic pre-pandemic lives. Matisse reminds us that we must retain what we might call the joy of the sedentary.

Like this, the art of the past has its messages. We must never forget what happened to Schiele, and to Klimt – and pay it appropriate respect and remembrance. But we must realise how superior a life of activity is, as shown by the advent of the Art Deco, while not forgetting that an abundance of energy, especially if it is misdirected, can lead to the horrors that Picasso depicted in La Guernica.

And if we look at Edith Schiele again, it is possible to look at her eyes and imagine that all this is somehow contained in those nearly hooded eyes. She sees us and doesn’t see us – just as we see and do not always recognise ourselves. But this is the help art gives us, as there is one sitting across from her – an artist who happens to be her husband – who gauges her with unusual intensity.

This is the privilege of art – to come from us, and yet somehow to know more than we do. When the art galleries open again post-pandemic there shall be wonderful things to see.